2024: The Year I Lost (the illusion of) Control

On doing the most and the least, and searching for the medium

A new study reports that 2.3% of US adults currently have activity-limiting long COVID. Granted: all the limitations of self-reporting studies, etc.

But still. That’s a wild number. That’s more than 7 million people.

Especially wild given how few people I’ve spoken to know much about it. I myself didn’t, either, until this fall. I had a vague understanding - I knew that it was the main reason to fear and strive to avoid infection, and re-infection, and that for some, it could be debilitating. But debilitating how? And how debilitating?

I didn’t go out of my way to learn because…because there were so many awful things happening in the world, because a person could come down with all sorts of illnesses but if you think about them all the time, what good comes of that? Because I wanted to keep living my life, unimpeded by fears of what might go wrong.

I didn’t know Long COVID is incurable and that we don’t know how it works in the body. I didn’t know how varied its presentation could be. I didn’t know young people tend to have it worse than older people, and women more than men. I knew almost nothing about ME/CFS, either - its potential severity, its disproportionate impact on women. And, relatedly, if just how little research has been done and money has been given to study the roots of it or find a cure, thanks in no small part to a history of sufferers being told “It’s all in your head.” I didn’t know ME is the only chronic illness actively worsened by increased movement and exertion.

If you’re interested in learning more about ME/CFS, I’d highly recommend the documentary UNREST by director Jennifer Brea.

Unsurprising, maybe, that people aren’t more well-informed. The people who know the most about it have the least energy to spare to advocate for treatment research or visibility or understanding. A cruel irony.

It’s a remarkable feat that Brea was able to direct a film about ME/CFS while suffering from a severe form of it.

Nate Bear’s recent Substack piece about my experience getting covid during my Arctic Circle residency caused quite a bit of online brouhaha - more than I expected, I’ll admit. Both in the broader online universe and in the group chat of artists from my residency, where there were expressions of sympathy as well as people who were upset - who think the ship and trip leaders did everything they could and should have been expected to do, who feared this kind of publicity could derail the residency. The most vocally upset was someone who did not get sick during the residency but reported to the group that she got covid a few weeks ago and was instructed by a doctor that there was no need for masking or Paxlovid, which was the same policy as the boat followed, and it’s terrible that I got long covid, but blaming the ship for not having tests or Paxlovid or asking symptomatic people to mask or isolate is irrational and untethered from science and medicine.

Then, on the flip side, we have X/Twitter —where Nate’s tweet of his piece had, last I checked, been reposted over a thousand times—there were tons of comments from people saying I got what was coming to me. That it was my fault, I should have known, who would ever get on a boat in a pandemic, I probably didn’t mask before during or after or care about anyone but myself. Many of these comments appeared to come from people who have lived in fully masked relative isolation since the start of the pandemic. It is true that, compared to them, I have lived recklessly. As recklessly as everyone else in my midst has, as governmental and social messaging has suggested I should. I did bring masks. I wore them on my flights. I could have worn them on the ship, but I didn’t.

Why? Because I was foolish? Because basically nobody else was. Because I didn’t want to.

It’s not the ship’s fault that I got Long Covid, of course. But I feel justified in frustration and disappointment about how they handled health on board. I do wish they had immediately tested anyone with symptoms and asked them to mask. I wish the doctor had Paxlovid.

What some of this blowback has underscored to me is that people - not all people, but some people, healthy people, people who have not been adversely affected by covid beyond mild symptoms - do not want to think about the ugly realities and risks of long covid, because to engage with it directly and deeply might lead them to question the safety of behavior they want to continue. Nobody wants to go back to masking, to testing before social gatherings. That was such a bummer.

Would knowing that 2.6% of Americans have activity limiting long covid have made me more likely to mask up? On the Arctic ship, in my daily life?

No. Probably not. Not unless everyone was. Not unless I had an underlying health condition that made me aware of the fragility of my health. I had an ableist perspective. I was healthy and I wanted to believe that I would continue to be so.

Imagine the fear and helplessness that would come of deeply considering all the ways you could suffer on any given outing. Car crashes. Viral exposure. Gun violence. You have no control — unless you stay home. Unless you shield yourself from the world. But is the improved physical health worth the emotional cost of that social isolation?

I don’t know how I will live or what precautions I will take if/when I return to being a person who exists regularly in the world outside my home. But it’s on my mind - as are broader thoughts about control and the lack thereof.

Usually, this time of year, I’d be thinking about resolutions and eagerly embracing the fresh notebook newly sharpened pencil feel of a new year. Less so this year.

2024 in Review

This year, I lost the illusion of control.

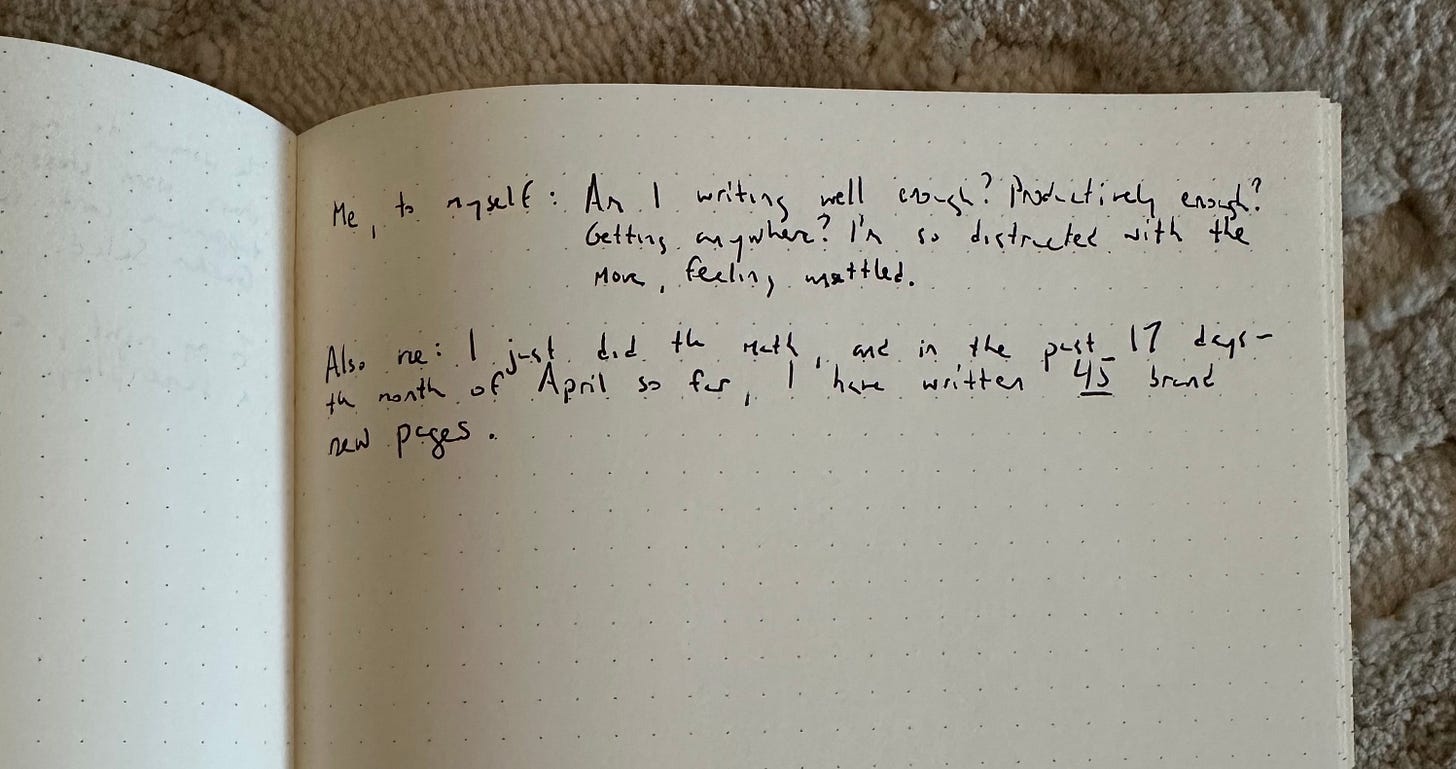

Recency bias is a bitch, and it would incline me to report that this has been a stalled year spent largely sick and in bed, because that’s how the past few months have been. But that’s one of the reasons I keep a journal and take notes - to remember things and to keep me from gaslighting myself.

Whatever the most self-critical conclusion I can draw is the one I’m inclined to reach. It’s funny how knowing this doesn’t help me stop doing it.

2024 was a year of extremes. Of both extraordinary productivity and its opposite. Far-flung adventure and extended isolation. Doing the most, then the least.

I started the year with a cross-country move from New York to LA. In February, I dove with dolphins and sharks and giant manta rays in an uninhabited Mexican archipelago a 26-hour boat ride from the nearest port. In March, I moved into a new house. In May, I traveled to Micronesia, where I woke at dawn to be a wallflower at a fish orgy, watching in awe as thousands of bumphead parrotfish congregated to mate. (Yes, I traveled around the world to swim in fish cum, and I wish I could do it again.) In August, I spent two weeks at sea in the Arctic Circle.

Professionally, I began the year by wading into more personal writing, starting with Ketamine Diaries, a 5-part series about my experience receiving ketamine treatment for depression. That was the beginning of my Substack experience; I had no idea who the writing would reach or how it would be received, and I was a little trepidatious about sharing so much of myself, but I’m glad I did. And it garnered a New Yorker mention! Which was wildly unexpected, given how limited my Substack subscriber base was at that point.

Name an antidepressant, I’ve probably been on it. Once upon a time, I felt uncomfortable with the idea of a pill altering my brain chemistry. Then I turned twelve and got over it. Anything to feel better. I have been continuously medicated for depression for 21 years now. Of all the medications I’ve tried, ketamine has worked the best, and the fastest.

Then, in a couple frenzied weeks, I wrote a nonfiction book proposal based on the Ketamine Diaries. One that I’m proud of and do think would make for an interesting book. My literary agent said this is good but please write me a fucking novel first.

I threw out 75% of the novel I’d spent the past two years working on and started over, with just 30 pages. And I wrote a fucking novel. I finished a messy draft by May and a more polished one by mid-September.

And then I crashed and spent October through December house-bound.

Doing nothing, I want to say — but that’s not true.

I taught myself to play ukulele. Am I good? No. Can I play One Direction’s “What Makes You Beautiful”? Yes. Is being a lefty a pain in the ass when it comes to teaching yourself instruments and crafts. So much yes. So many “just learn to do it right-handed” posts written by ignorant righties.

I re-taught myself how to crochet and advanced beyond basic stitches for the first time. I made two blankets, two vests, one top, one shawl, three scarves, and ten hats.

“I don’t have the energy/can’t think clearly enough to do any real writing because of long covid,” I admonished myself, while writing and publishing about 12,000 words about having long covid.

Cognitive dissonance is a real bitch.

My 2025 resolution: Pace myself.

There’s a lot of talk about pacing in the online long covid and ME/CFS community.

Pacing is about limiting exertion, learning exactly how much your body can handle and how much every activity costs. People in the chronic illness community often refer to spoons - how much spoons an activity costs, how many spoons they have available.

A healthy person doesn’t have to think like this. Like all forms of exertion involve a net loss. Activity being rejuvenating or restorative? No way, not anymore. Everything - even the things you enjoy most - has a cost.

I’ve been learning about those costs, in part with the help of Visible, an app created specifically to help people with long Covid and ME/CFS assess the energy costs of their daily activities and pace themselves accordingly. The company describes itself as a “wearable platform for illness, not fitness.”

Exertion is measured by heart rate monitoring and self-reported symptoms, and a daily “PacePoints” budget is computed based on your personal data. The idea being that if you stay under the daily budget, you are likely to avoid crashing. There are limitations to this method. Social, emotional, and cognitive exertion don’t involve an increased heart rate and are harder to quantify. But it’s a starting point. And for a newly sick person, it’s a helpful way to wrap your head around this new way of thinking.

I’ve worn two, sometimes three trackers for the past two months - a Garmin watch, the Polar Sense armband monitor that works with the Visible app, and an Oura ring. I’ve become hyper-aware of my heart rate and bodily stress. Through these systems, I’ve learned that, for example, a seated shower costs about 8% of my daily energy budget.

“-1 Body Battery point,” my Garmin watch informed me after I finished a twenty-minute meditation session.

The Garmin watch is designed for people who benefit from regular standing and movement. I had to turn off the notifications urging me to get up and move around every hour. Still, at the end of the day, the watch would issue a daily recap: You had an easy day, or you had a balanced day, or you had a stressful day. It often complimented me for exercising (I hadn’t), or predicted that I had plenty of energy left to do some yoga or other exercise before bed (I didn’t.) But unlike my armband, it calculated my heart rate variability (HRV) continuously and tracked my sleep. Visible assesses HRV only once a day. You’re supposed to put the armband on in the morning, before getting out of bed, and then, using the phone app, prompt it to take a reading, which will then produce a Stability Score for the day - 1 to 5, 5 being the best. I got a 4 maybe once. Usually it was 2 or 3. You’re trending away from your baseline, it would warn me. Meaning my resting heart rate was high or my HRV was low. There’s some data suggesting that a lower HRV can predict an oncoming crash. Pace yourself carefully today, the app counseled.

Meanwhile, my watch wished me good morning, with a weather forecast and a breakdown of how long and well I slept the night before. Once in a rare while, it said “Plenty of REM.” More often, no matter how many hours logged, the sleep was graded “Non-restorative.” Not enough deep sleep. My watch also took the liberty of sending me headlines from Reddit groups it thought I might like.

Visible assigned me 12 PacePoints per day. On one recent day, I was frustrated to find that, by 10am, I had already used up 4 points. The app warned me, through a notification on my phone that was also broadcast on my watch, that I was likely to go over budget at that rate. I considered my morning’s activity: a walk from bedroom to kitchen to make a coffee I drank while reclining. A seated shower. About ten minutes playing tug with my dog on the floor. That was it.

Visible requires the armband to be within a certain limited distance of your phone so that your phone can alert you if you’ve spent a certain amount of time in the “exertion zone” and encourage you to slow down. Because my watch was connected to my phone, I could also get those notifications on my watch, but only if my phone was nearby. I spent my day shackled to these devices, consulting them like a bible. Feeling defeated and frustrated when I burned through points while doing next to nothing. Uncertain about what to do when I hit my budget at 5pm. Straight to bed? Lie in the dark? What about washing my face, brushing my teeth, changing into pajamas?

My exertion zone started at 109 heartbeats per minute. (It was previously called the over-exertion zone; the app did a recent name change because some people, depending on their health, can afford to spend more time in the exertion zone, making “over” a misnomer.) My resting zone was under 79. In between, the activity zone. The more time spent in exertion, the faster I’d burn through points. Keeping my heart rate under 109 might seem feasible enough, but because of POTS, when I stand, my heart rate jumps immediately to 100. If I start doing anything, it continues to climb.

Carefully following my PacePoints consumption and heart rate fluctuations was helpful until it wasn’t. Until I realized that the time I spend checking the watch and the app is itself a form of exertion.

A few days ago, I hit a breaking point. I took off my trackers.

It’s been a relief, so far, to be without the data. It requires me to listen to my body more, as opposed to outsourcing to my phone. But I think I have enough of an idea now of how much what costs to gauge what I can reasonably do - at least when it comes to physical exertion. I still don’t know how to estimate social, cognitive, and emotional exertion. Crashes come at a high cost. They can last days or weeks or more, and repeated crashes can erode baseline function. I still haven’t returned to the level of capacity I was at before I crashed in mid-October.

Does the cost of socializing outweigh the emotional cost of isolation? How much socializing can I safely do? How much thinking? How much writing? It’s frustrating and strange to actively limit how hard and long I think. To search for activities that require just the right amount of brain-power.

For the first year in my life, as I look to the year ahead, my goal is to do less, not more.

And also, to not think of the year ahead as a whole.

Taking a broad view of the year would involve thinking about the prospect of ongoing illness and incapacity. The emotional exertion involved in contemplating more activity-limited months at home? Too much.

Anything - or, if not anything, many things - could happen. Very little of it is within my control. It never has been. The only difference is my cognizance, for better and worse.

Except: here I am, writing about it, partly in order to reclaim control. I, like most writers, am a control freak. I write to understand, to connect, and to reclaim agency over situations in which I felt I had none. If a bad experience can be transformed into good material, it becomes a little less bad. So yes, must acknowledge the irony of writing about losing control while also trying to wrench it back.

And now, my brain - but not my phone or watch - is telling me: enough. And I am listening. Listening and doing the wildly uncomfortable: sending this out without revision, hoping you’ll cut me some slack on repetition or sentences that might have been tightened.

I know how to do the most and the least. Still learning how to find the medium.

By sharing the info from your trackers, you’ve given everyone who reads this a much clearer understanding of what you and other long Covid-sufferers are going through. I knew it was bad, but seeing the data made my jaw drop. I’m so sorry this is happening to you.

It’s funny (not funny) - I was reading your section on trackers and was thinking I’d comment that after you learn your body’s rhythms through such tools, take them all off and stop watching your body like a hawk. This just keeps your brain (and hence, your nervous system) on high alert. I used the Visible armband and my FitBit for a good few months toward the end of 2023 and I learned a lot. I had been way overdoing things before I had these trackers. The trackers helped me get into a better window of energy use that I have been able to sustain since (with a few slip ups here and there). I’ve made solid gains in the last two years, and I attribute that to pacing and working on keeping my nervous system in a state of calm and joy. I watched a ton of recovery videos on Raelan Agle’s YouTube channel too. That kept my brain hopeful, which was a big help too. Good luck with everything! I hope you see improvements in 2025.