I can’t see straight — again.

On learning to draw with vision problems, Frida Kahlo, adaptation, and painting from bed.

I can’t see straight. Again. I have the most trouble clearly seeing what’s right before my eyes - say, a pen or finger as it approaches my nose.

(Metaphorically, it’s almost embarrassing. Too on the nose.)

The problem is called convergence insufficiency, and it’s a type of binocular vision dysfunction. When tracking inward, my left eye does fine and my right eye…doesn’t follow. Like so many of my recent health issues, it’s something I had never heard of before and would therefore not have suspected I had.

So, in case anyone reading this has experienced similar mystery symptoms, I want to share my personal experience of how it manifested in me and what it impacted. Because according to the Cleveland Clinic, it affects between 2 and 13% of people in the US. Mostly children, evidently. Or it most often starts in childhood. But it also impacts adults, with causes ranging from prolonged overwork possibly impacting more adults due to causes ranging from computer eye strain to covid. For me it’s a post-covid problem, presumably connected to my other nervous system issues, since it involves an optic nerve malfunctioning.

And then I’ll move on to more fun things like my new DIY portable painting setup that allows me to paint lying down.

(If that doesn’t sound categorizable as “fun” to you, remember: I’ve been forced to develop a more broad definition of “fun” in order to have any.)

*

What I noticed first, this summer: jumping words. I noticed it initially while reading on a Kindle, but it wasn’t screen-specific. Not double vision, but like the letters were dancing and took a little time to settle into place.

That was it, the only obvious symptom. But it made reading a little dizzying and uncomfortable.

I discovered that if I kept my (new, distance only) glasses on while reading, the problem wasn’t as bad. Eventually my brain corrected for it so that the words no longer jumped; the only remaining symptom was that…I didn’t want to read as much anymore. It was too tiring. Not enjoyable. No matter what the subject.

Which for me was a huge problem because words - reading and writing them - are and have been my lifeline for so long. It’s how I spend my days, how I make sense of the world, how I conceive of myself.

But when you have ME/CFS, it can be hard to pin down cause and effect. All sorts of activities can become draining if I’m in a crash (a state of reduced functionality following even mild over-exertion…e.g. the week I just spent mostly bed-bound after over-doing it with about 1 hour in a car).

I went to the eye doctor. My ophthalmologist referred me to a specialist; said neuro-ophthalmology specialist was booked out for months. I have an appointment scheduled for mid-November.

In the meantime, there were the nerve blocks. And the nerve block doctor said this was a problem he could fix. The stellate ganglion blocks, after all, dilate the blood vessels in the brain and reduce neural inflammation, and this being an optic nerve problem…well, it made sense to me. And, after the third set of SGBs, my eyes DID converge again! Magic!

The trouble was, by day three, I found myself in a severe crash, newly sensitive to sound, perma-exhausted. I didn’t have the energy to read, to take advantage of my eyes’ new ability to converge.

I could still draw, but for shorter periods. I could only read a few pages of a book or watch a few minutes of a tutorial video at a time, which made learning tough.

Adaptation and self-expression

I started drawing in earnest in July. My new interest in drawing aligned with my new difficulty reading and writing. I clearly needed some form of analog mark-making in my life, as a tool for processing the world and my experience in it.

Drawing was an imperfect substitution for writing because…I have no art training.

I took Drawing 1 in eighth grade. I wanted very badly to have visual artistic talent. But at that point I knew how it felt to have a natural aptitude for something (and how others responded when you demonstrated it). I knew I didn’t have *it* for drawing, or, presumably, painting.

I was 14; I wanted to excel; I had so many feelings I needed to excise; I found less satisfaction in a medium where technical incompetence bottlenecked my capacity for self-expression. I redoubled my focus on words. (In retrospect, I suspect my biggest problem was an inability to get out of my head and draw what I actually saw vs what my brain thought I was seeing.)

Anyway. I’m not 14 anymore.

And among the many ways I’ve changed since 14, I have become - I realized the other day, with surprise and some pride - extremely adaptable.

I have adapted to things I never could have imagined. And I continue to adapt.

Before this past year, before getting very sick, I would have called myself resilient. I knew I could bounce back from a lot. But resilience is different than adaptability. Note to universe and body: this is not an invitation; I don’t need to test this skill much further. I’d love to exercise this in adapting to improving conditions. But in the past few months, that wasn’t my luck.

I’ve learned that sometimes my body or subconscious understands what my capacities are before my conscious self does. I’ll feel a general aversion towards something - and I know, now, to interpret said aversion as my body saying, “that costs too much energy; the costs exceed the benefits.” Reading and writing went on the list.

I’m writing now - I still feel the need spill over sometimes; and sometimes I have the battery capacity to do it. (I haven’t yet learned to pace myself, so I have to be careful. It’s either zero words or thousands of words.) I do know to write on a computer. It’s my less preferred medium, because I think differently (better) with pen and paper. But keyboard costs less, energetically. And I find that when I write in a burst and then limit my activity for the rest of the day - sometimes the benefit exceeds the cost.

*

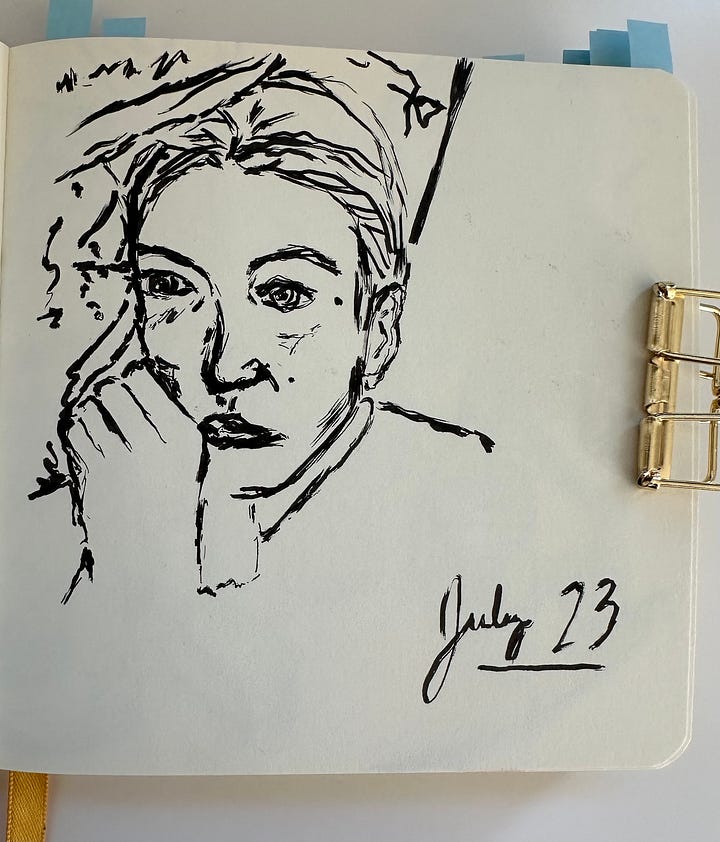

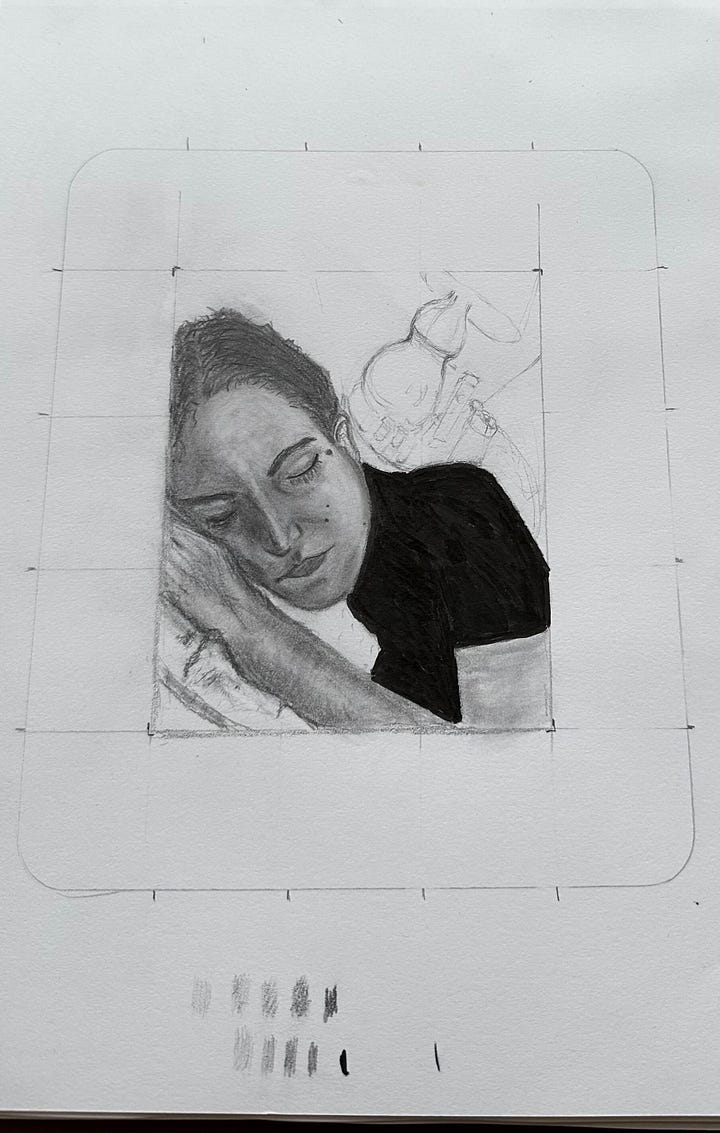

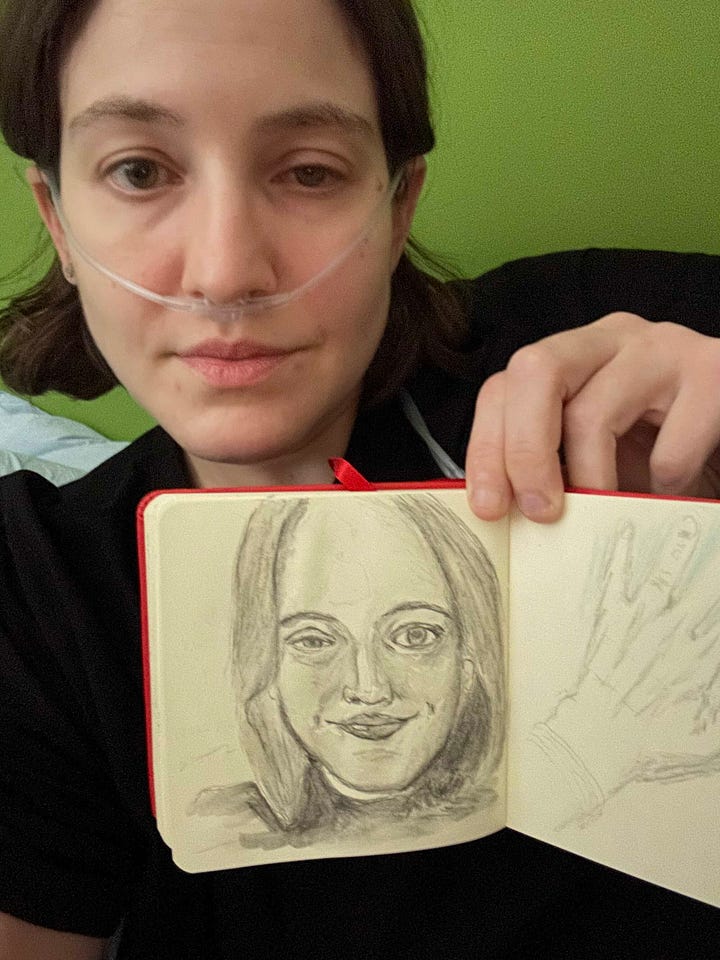

This summer and into the fall, I tried to improve my self-portraiture. Tried to learn how to see myself - and my feelings - in an entirely new way, one that I could express visually instead of verbally.

It is hard to be a beginner at anything.

It is hard to be a beginner as an adult.

It is hard to be a beginner with an energy-limiting illness.

It is hard to be a beginner who must pace and accept slow progress when used to taking an obsessive all-in approach.

I’m not sharing these sketches because I think they’re “good.” I’m sharing them because I’m learning that being “good” at something matters less than I once thought it did.

One month post-nerve block update

It has now been one month since my last nerve block. I still have no idea what is going on in my body. My baseline functional capacity is still lower than it was a few months ago. I am resting, trying to let my body restore itself without further intervention. I’m meditating. My voice is gradually returning. My breath capacity is also gradually improving. My tolerance for sound is not as limited as it was, though it has not improved to the point where I can, say, watch a TV show. I am listening to audiobooks with soothing narrators in small chunks.

I’ve been having more trouble with drawing lately, though. I didn’t understand. Hitting a plateau? Why wasn’t my perspective improving? My depth perception so off? Why couldn’t I draw an approximately straight and level line?

The other day, I was trying to make a video demonstrating the one unqualified positive outcome from the nerve blocks - the eye convergence. That was how I discovered that they no longer converge. And that was when I understood why I’ve been struggling with drawing. Until then, I just thought I was struggling because of general fatigue and limited learning capacity.

But no. Lo and behold: I can’t see straight again. Convergence insufficiency impairs my depth perception. It makes it even more exhausting to draw from life, to interpret angles and spatial relationships, than it would otherwise be. My brain is working too hard, my eyes aren’t working well together. And my brain can no longer afford to work as hard or as long as it could in the summer, when I began drawing.

Time to adapt, again.

Time to focus not on lines and perspective and accuracy…how about color? I’ve always wanted to paint. I bought a set of watercolors months ago but rarely used them because it turns out painting is emphatically not a lying down activity.

I can’t work upright at a table for very long, but I was determined to find a workaround. I scoured the internet for some magic device, googled things like “chronic illness painting from bed setup?”

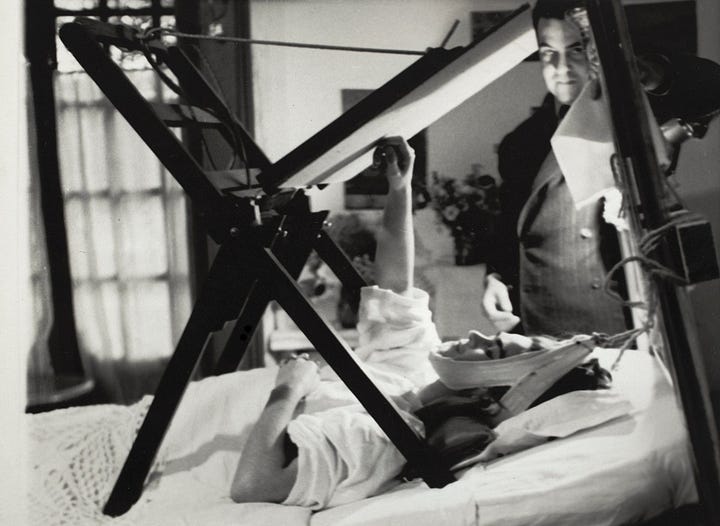

This yielded impressive stories and photos of Frida Kahlo painting from bed.

At age 18, Frida Kahlo suffered severe, life-altering injuries in a bus-hits-trolley-car accident. In the aftermath, she was immobilized by a full body cast and bed-bound for months. I learned the story of the bus accident during a visit to a Kahlo exhibition at the Brooklyn Museum in 2019. I remember seeing her painted plaster corsets. What I didn’t remember - if indeed it was included in the exhibition’s materials - was that before the accident, Kahlo had never painted or expressed interest in becoming an artist. This detail I only just learned.

During her convalescence, her parents set up a special easel she could use lying down and mounted a mirror above her bed so she could see her face. While almost entirely immobilized and isolated, she taught herself to paint, painted her first self-portrait, and learned to transmute pain into art. The rest is history, and so on.

For the rest of her life as an artist, she turned her creative eye toward pain - specifically her personal pain - forcing viewers to confront what people try so hard to avoid looking at directly. There’s so much I want to write about that - about art and writing about illness and disability; about how it is received as well as produced, but I don’t have the energy right now, so it’ll have to wait for another day.

“I paint self-portraits because I am so often alone, because I am the person I know best.” - Frida Kahlo

To be clear: I’m no Frida Kahlo. I’m pretty sure this illness is not going to transform me into a brilliant painter. I certainly have turned my creative eye toward pain this past year, though, pushing past concerns that people must be tired of hearing about it, that, as Alphonse Daudet wrote in In the Land of Pain, and as Meghan O’Rourke quoted in The Invisible Kingdom, “Pain is always ‘new’ to the sufferer but loses its originality for those around him…Everyone will get used to it except me.”

What I’ve learned is: people have a strange Pavlovian PTSD I don’t know what it is reaction to hearing the c-word. No, not that one. Covid. And that includes Long Covid. They somehow can’t or won’t focus on it - not enough to internalize the warnings I and others are trying to shout as clearly as we can: Long Covid is NOT just having Covid for a long time! The more times you have (mild) covid, the higher your risk of getting Long Covid ! Women are at 30% greater risk than men! 50% of people with Long Covid meet the criteria for ME/CFS, a currently incurable illness that leaves 75% of sufferers unable to work and 25% house/bedbound!

And now, in bold, because it’s NEW news and I know plenty of people reading this are parents and may think children are generally at lower risk: a new study from UPenn found that a second covid infection DOUBLES a child’s risk of Long Covid.

“Pediatric patients who had COVID twice were more than 3.5 times as likely to develop myocarditis, a swelling of heart muscle that can weaken the heart and be life threatening. After that, the next greatest risk to pediatric patients after a second COVID infection was a doubling of their chance of developing blood clots.

In addition, the risks of developing severely damaged kidneys, abnormal heartbeats, heart disease, and severe fatigue all were significantly more likely with a second COVID infection”

Sorry. This was supposed to be mostly a semi-light piece about my amateur art journey. I couldn’t help myself. Back to art-making….

I couldn’t find a contraption to purchase online that would make painting a more accessible activity, so I - not traditionally a very DIY person when it comes to this sort of thing - decided to get a little crafty.

With the assistance of a dry-erase board, magnetic tape, no-spill cups designed for children’s paints, and metal tins, I made myself a portable magnetic painting board that I can easily move from couch to bed and switch locations while using.

Have I spent more time setting up paints this week than using them? Yes.

Has it felt good to have the capacity to solve a problem (no matter how small, in the scheme of my problems)? Yes.

Does this mean I can paint for hours now? No. Other limitations still apply. But I’m trying to adapt. One step at a time.

Sharing a video of my setup here, in case this inspires anybody else!

Presenting…my DIY magnetic paint-from-bed-or-anywhere board.

A Beginner’s Mindset

I don’t expect to become a master painter.

My default toward learning used to be an intention to master [fill in the blank]. I go all-in. I know myself to be an indefatigable learner and worker.

Went. Knew. Was.

That has all changed profoundly in the past year. My body’s energetic limitations rule my days, shape my plans.

I’m coming to understand that it isn’t always about being “good.”

What matters is the act of creating. Of developing the capacity to do something I couldn’t do before. It’s an important reminder of neuroplasticity, of my brain and body’s capacity for positive as well as negative adaptation.

It is a way of expressing, and feeling: I am here; I am doing; I am making. I am growing, in spite of - and in some ways because of - it all.

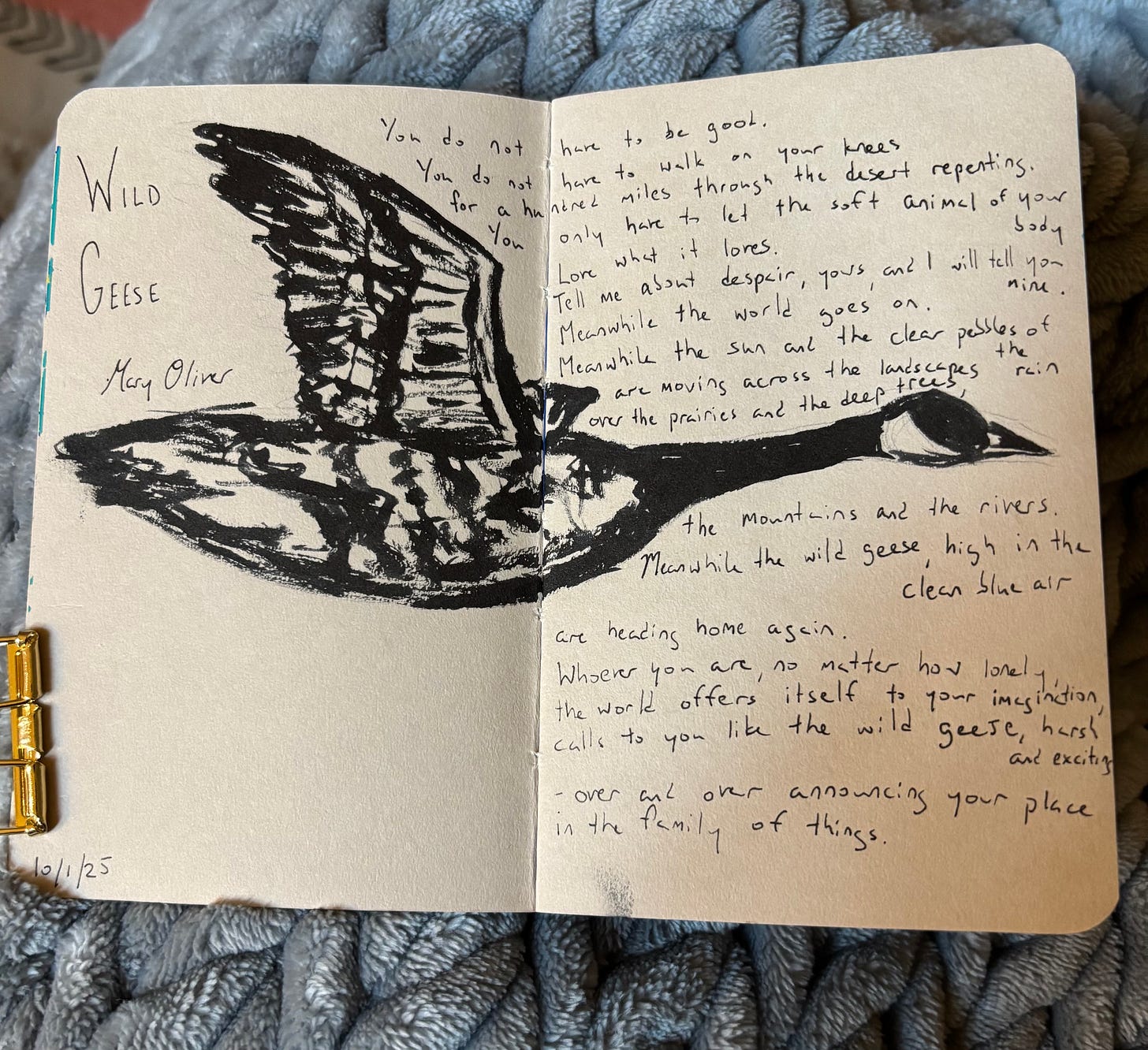

(“Wild Geese” is one of my Mary Oliver favorites. If you don’t know it and can’t read my handwriting, here’s a link to Mary Oliver reading the poem aloud.)

x Isabel

Necessity is the mother of invention, right? (And long covid is one mother of an illness.) Very cool Frida-inspired system you rigged up. Curious if you plan to emulate her in the eyebrow department too. You know, just for kicks.

I think your drawings are quite good and have no choice but to revoke your membership to the People With No Visual Artistic Talent Society. We’ll miss you at the meetings.

Here's a suggestion for another type of accessible art set-up that I've found helpful: a screenless drawing tablet (wacom intuos or similar) hooked up to a computer screen that's set at the right angle. The stylus and the brush output are not coupled together, meaning you don't have to look at your hands when painting. The screen can be set farther away, beyond comfortable arm reach, which might help. You can set the tablet on your lap in bed fairly easily. Also you don't have to deal with a complicated set up or clean up routine.

Wishing you the best.