I’ve been relieved to see discussion about air toxicity and health risks in LA increasing over the past few days. Shortly after I sent out my last newsletter, The Guardian published “Where there’s fire, there’s smoke: Los Angeles blazes raise fears of ‘super toxic’ lung damage”

Then, on the 14th, The Washington Post published “Here are the toxic threats that emerge after an urban wildfire”

From that article, an aspect I haven’t seen emphasized as much elsewhere:

In the home, particles can settle on the ground or on the walls, while VOCs can be absorbed by any surface, such as furniture, Habre said.

“They tend to stay there and get remitted into the air when it’s a little bit warmer, and then they go back and stick into surfaces or particles,” Habre said. VOCs are “in general more toxic than particles,” she added.

VOCs are “trickier,” because they stick to surfaces and aren’t filtered through air filters, Habre said. Without proper surface cleaning — washing surfaces and linens with non-fragranced soap and water — the compounds can loft back into the air.

Finally, today - January 16th - The LA Times published their equivalent piece. Its headline is considerably less charged: “The long-term health effects of L.A. County wildfire smoke”

The L.A. wildfires have coincided with a 16-fold rise in hospital visits for fire-related injuries, such as burns and smoke exposure.

Although the smoke’s immediate effect has begun to dissipate, lingering ash and toxic chemicals in burn areas probably will be a long-term public health concern.

Probably will be a long-term public health concern

Note that the first piece came from a foreign newspaper, and the mildest phrasing and framing comes from our local paper. Coincidence? I think not, for reasons I’ll get into below.

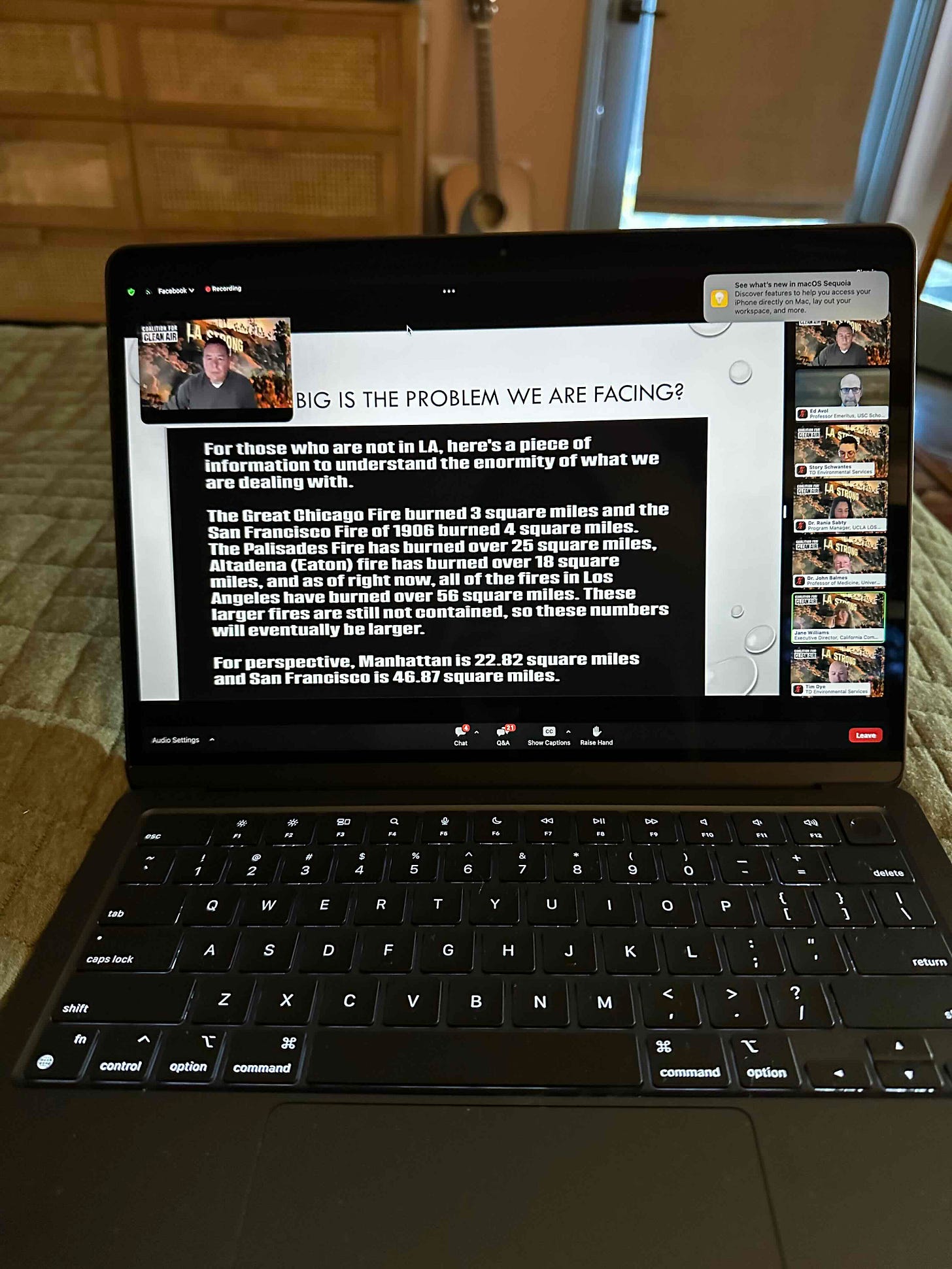

Yesterday, I attended a webinar hosted by the Coalition for Clean Air, featuring a group of scientific experts speaking on and answering questions about air safety in LA.

The area that has burned in LA is the equivalent of basically 2.5 Manhattans. Or all of San Francisco plus half of Manhattan.

9/11 and its after-effects on health were mentioned as a public health disaster to learn from, but the scale of this is so much bigger. More apt, one of the presenters said, would be comparing it to a city bombed out in wartime.

And when cities are bombed during wars, generally the civilian population is evacuated first, the speaker noted. So there’s limited data about the health effects on civilians.

Also - though this is me extrapolating, not paraphrasing a speaker - when the U.S. has bombed a city, we haven’t been particularly interested in tracking the long-term health impact of said bombing on that city’s population.

The term the Coalition for Clean Air’s speakers used for what’s happening now and in the months to come is the disaster after the disaster.

The most specific timeline offered: It will likely take 1-2 years to excavate and remove all the ash. Years. And each time a site is cleaned, if proper precautions are not taken, the activity might reintroduce toxic ash and chemicals into the air.

The experts warned about politicization and the likelihood of officials underplaying certain risk factors in an attempt to “get back to normal.” They pulled up The Guardian article I quoted Christine Todd Whitman from in my most recent newsletter, in which she expressed remorse for assuring New Yorkers that the air and water was safe so soon after 9/11.

Nobody wants to hear that it’s going to take up to two years to clear the ash, and that if you live anywhere near the burned zones, each time a specific site is cleaned out, and each time the wind blows, there is a risk of ash being reintroduced into the air.

Much of what I learned in my independent research about AQI was reiterated - that AQI has utility in its capacity to measure small particles generally, but that it can’t detect the toxics in the air, such as the ones of greatest concern now. Those generally aren’t tested at all because the testing is so expensive.

One speaker said AQI is a decent proxy for air quality. Another - an expert on air toxics - said not so fast, that doesn’t measure the toxics. Another pointed out that the dangerous toxics do end up sticking to the particulates that are measured by AQI, which will make AQI a relevant measure. BUT also, don’t forget: the wind.

A question many had was: how far away do I have to go for the air to be “safe”? The experts carefully avoided naming any number of miles. It depends on the winds, depends on the day. Honest, if vague and of limited comfort to those of us who aren’t well-versed in reading the winds.

Two years to excavate the ash is a number we almost certainly won’t hear from any city official. Because: can you imagine the upheaval? The impact on the local economy if people decide to leave LA en masse? If people in adjacent neighborhoods with still-standing homes begin worrying about the safety of staying in them?

But even if city officials were to acknowledge just how long ash removal is likely to take, which they won’t, but let’s imagine them doing that — or, no, that’s too much of a stretch. Let’s, instead, imagine them emphasizing the risks and encouraging people to refrain from returning home immediately if they can afford not to. Especially if they have children or are pregnant or elderly or have respiratory or cardiovascular problems.

Well, even then, people would be compelled to return.

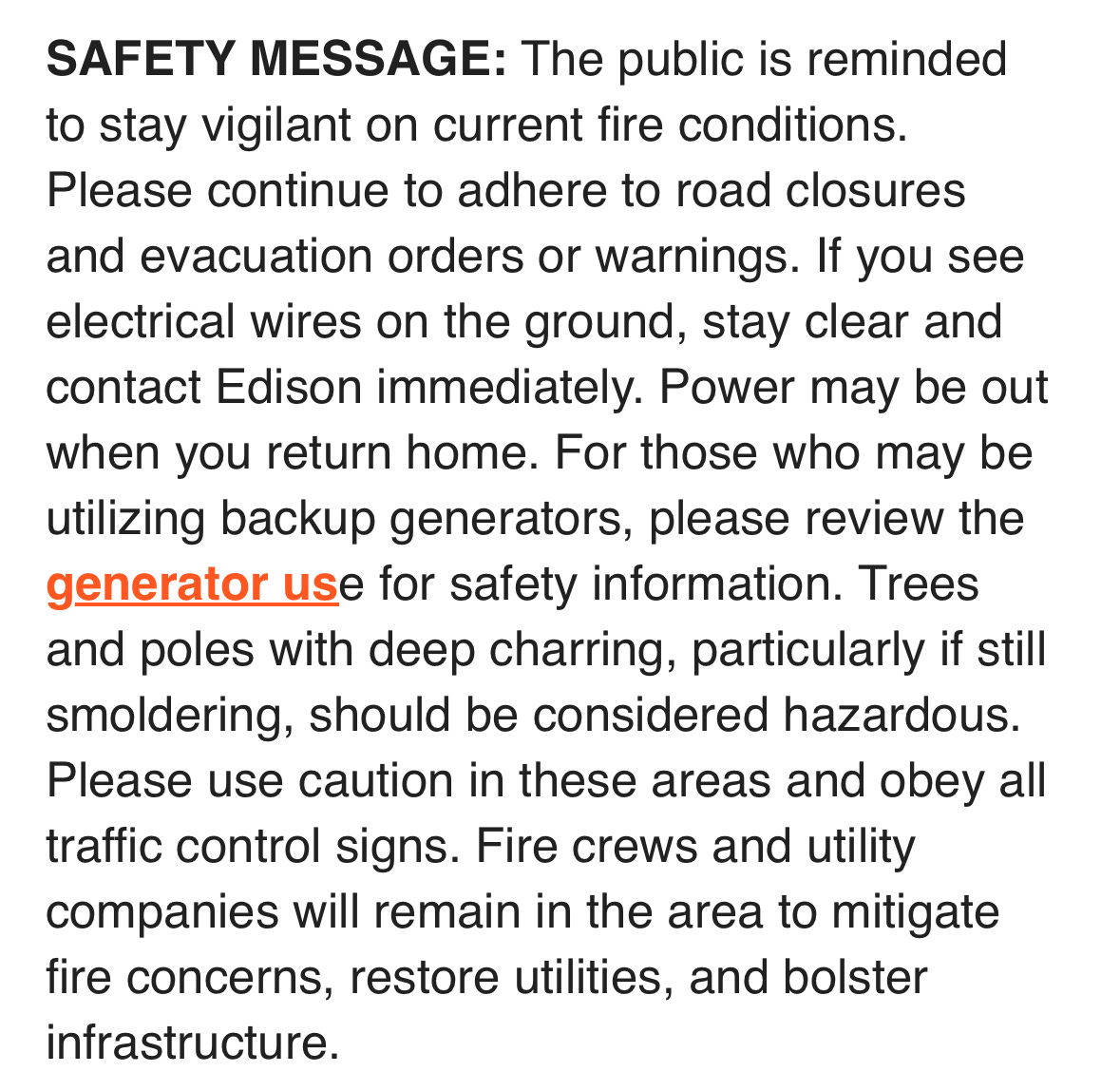

While typing this, I received a notification from the Watch Duty app, announcing a partial repopulation of some areas evacuated for the Palisades Fire. No mention of health dangers from the air/ash/debris or encouragement to wear PPE in the attendant Safety Message.

The sociological drive to return home and return to normal is powerful to the point of irrational.

One of the speakers offered the aftermath of the Maui fires in Lahaina as an example. Government officials stationed guards outside burned areas to prevent people from returning home. They were told why they should stay away: for their health. And yet. A bunch of locals bought all-black clothing from thrift stores in order to sneak through at night undetected.

We have already witnessed similar here in LA. People desperate to get back to check on their homes even before the fires are significantly contained. That’s why it’s so important to talk about risk mitigation.

People are going to return to these areas whether they are advised to do so or not. The most officials and the community can and must do is to emphasize the dangers and reiterate the ways people can protect themselves - over and over again until there is some semblance of social pressure to comply.

So, one more time for anyone just tuning in now: if you MUST go back to a burned area in the near future: cover up fully. Wear goggles, a P100 or N100 mask, gloves (strong, cut-resistant ones), a Tyvek suit or at least long sleeves and pants, and sturdy footwear.

Then take off all of those things after you leave the site, to avoid bringing contaminants with you. Also, make sure you’re up to date on tetanus vaccines.

In the greater LA area: mask up outside (N95 at minimum, but preferably N100 or P100), and purify your air inside, ideally with a HEPA MERV 13 + filter . If you’d rather take a doctor’s word for it than mine (don’t blame you!) - here’s an ER physician saying the same on Fox 11 yesterday.

Plenty of people are going to be eager to report that the air is getting better. See, for example, a Reuters piece from today: “Los Angeles air quality improves from wildfires’ hazardous levels.”

Through my window: clear blue sky, mid-afternoon sun, palm tree with fronds swaying gently in the breeze.

It certainly looks nice out.

But as anyone from LA should know, looks can be deceiving.

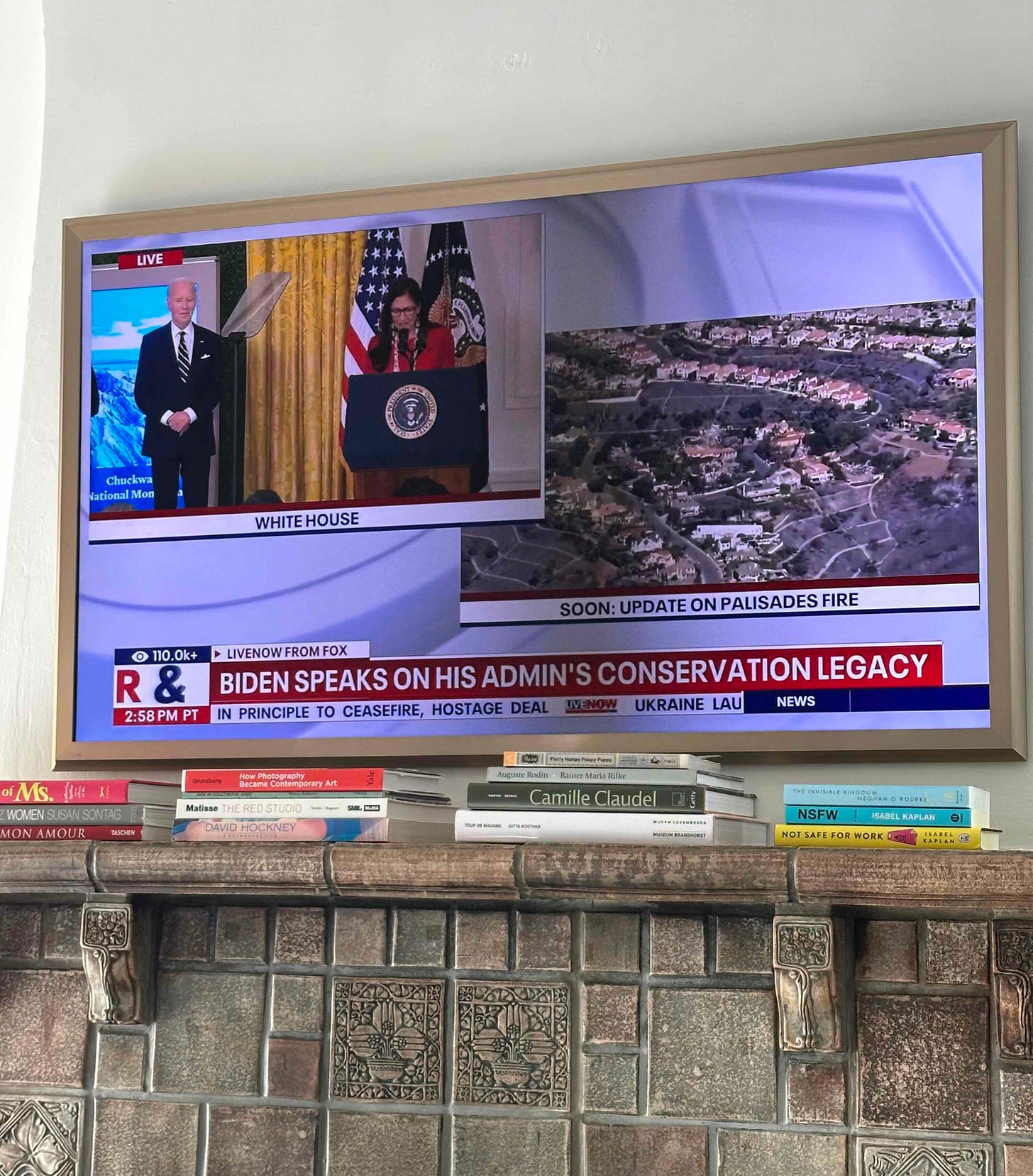

Finally, I’ll conclude with a funny slash depressing screen grab from the other day: