Thank you for all the positive responses to part 1, and for the encouragement to keep going — there is no way to say it without sounding trite, but it really does mean a lot to me. Alarmist headlines about ketamine continue to proliferate — eg yesterday, the Hollywood Reporter posted “Matthew Perry’s Overdose: Will It ‘Villainize’ Ketamine Treatment?” along with an opinion piece entitled “My Ketamine Clinic Visit Was Absolutely Terrifying.” Warning that more problematic medical behavior is to come here, but if you stick around, there will be light at the end of the tunnel. If you missed Part 1, you can find that here.

We left off with me waking up from a ketamine trip alone in Dr. K’s office and noticing the drug shelf across from me filled with bottles of ketamine, syringes, even a blank prescription pad. I saw the package of lozenges with my name and slipped it into my bag before leaving.

If you prefer your recaps in video form and/or would like to see what I’m like when coming down from Ketamine —

As I left the building, I saw Dr K standing by his car, reading something with the driver door open. He looked like a man killing time. I considered going over to him, then decided against it.

I sent a furious text. He didn’t respond. He finally called the next night, said he’d had an emergency, a patient had overdosed and was in the hospital, he had to make a call. I wish I had asked why he needed to leave the building to make a phone call. Or why he wouldn’t make sure the receptionist was staying in the office before he left. Or pointed out that he responded to one patient’s emergency borne of unsupervised drug use by leaving another patient to…unsupervised drug use, in a room full of unsupervised drugs. Or that I’d seen him out by his car, and he wasn’t on the phone.

He promised it wouldn’t happen again.

I had a vacation scheduled for the following week, which I had booked before deciding to do ketamine. It was a weeklong liveaboard on a diving boat in Belize. Dr. K had said it would be okay to do half of my treatments before and half of them after.

By serious scuba diver standards, I’m a beginner. I have my Advanced certification but am still shy of 100 dives (though I’m getting close). To non-divers, I’m aware that 100 sounds like a lot, but some of the people who do liveaboards log 100 dives in a year.

I love being underwater; I always have. Underwater, I feel free, exultant, weightless. I could wax poetic about my love of diving for a long time but I will forcibly restrain myself and save that for another time. The point is: I was excited to spend a week diving in Belize. And a week entirely off grid– there would be no cell service throughout the trip.

I wish I could take everyone I know diving, but as it happens, basically nobody I know is a diver, so it’s an activity I’ve gotten used to doing on my own/with strangers. There were about twelve other divers on the boat, a few of them around my age, including a honeymooning couple and an American guy a few years younger than me. We’ll call him John. He was traveling with his dad, and they invited me to join their dive group for the week, meaning we would be responsible for each other’s underwater safety.

John and I found ourselves alone on the boat’s top deck one night, early in the week. Flag rippling on its pole, sky gaudy with stars. My hair was damp, my face and feet bare. I felt young and carefree and grateful. I lay down on a padded bench to look up at the sky. John lay down next to me. I pretended to focus on the sky. Watched him inch his fingers closer until they touched mine.

*

After, I climbed down to my cabin, thinking: that was fun.

Just that was fun.

Do you know how often I have only a single thought about any given experience? Never.

This continued for the rest of the week – both the running around with John and the thinking and feeling one thing at a time. When I was diving, I was fully immersed in the dive. I stared with wonder into the eyes of a grouper.1 I exhaled slowly to descend to a safe distance from a black-tip shark. I watched bioluminescent jellyfish float by in the dark of a night dive. I listened to my body’s needs and didn’t question them. When I was hungry, I ate. When I was tired, I napped.

Maybe this sounds unremarkable to you. Maybe you’re familiar with what it’s like to live in the moment. I’m very happy for you. I mean it. I see what the fuss is about now.

Prior to this, I was much more familiar with ordering myself to be in the moment than actually achieving it. Usually I live in about four to six moments, give or take. The past, the present, a hypothetical future or two, and then the world of whatever writing I’m currently working on.

This new mindset was so unlike me, I understood immediately: it had to be the ketamine.

Now, you may say: it’s easy to feel like this on vacation. And I’d agree that it’s certainly easier to feel like this on vacation than in ‘real life.’ But I am eminently capable of overthinking myself through vacation, too.

Ketamine allowed me to enjoy the week without getting trapped in thought spirals like “okay but what are you doing with your life after this week?” or “you realize that though you’ve found this activity you enjoy more than almost anything, it’s inconvenient and expensive and you probably won’t get to do it again for who knows how long, right?” or “are you and John on the same page about what you’re doing here?”

Usually, I have thoughts like that and then tell myself not to think them before continuing to think them, but now with an extra bonus helping of disappointment in my lack of self-control.

Now, life felt simple and easy and fun. Sometimes it’s not complicated, I told myself. I’m on vacation; I’m enjoying myself at sea; I’m having a casual summer fling. That’s it.

Sometimes there isn’t a catch.

It’s not like I wanted to keep seeing Dr. K.

But I didn’t know any other ketamine doctors. I assumed finding a new one would take time, and I wanted to finish my treatment series ASAP. If just four sessions had boosted my mood this much, imagine what six could do!

So back to Dr. K’s I went.

*

Is this the right place to mention that Dr. K had writerly ambitions?

It’s an LA stereotype, that everybody has a screenplay in them - even your doctor. And sometimes it’s true. I think Dr. K considers himself more of a prose writer, though. I’m fuzzy on the details because they were dispersed largely while I was on ketamine. He took a writing class with the guy who broke his car’s rearview mirror. He wrote a short story about cannibals and mad cow disease. He admired me for writing books. I believe he thought we had something of a literary connection.

This is maybe also a good place to clarify that Dr. K treated my mother and me differently. He offered her a ride home once, after her last session. But he didn’t leave her alone in the office or send her playlists or offer to introduce her to his friends or bring in books to lend her or send rambling half-incoherent late night texts (we’re getting there).

What did this fifty-something doctor want with me, from me?

There is a distinctly heteronormative dynamic in which a man bobs gleefully in the grey sea of ambiguity while a woman labors over his coordinates in an attempt to locate him and legitimize her discomfort.

I felt uncomfortable around Dr. K. It was easy to point out him abandoning me in the office as a reason for my discomfort. But that wasn’t all of it. It was just the only part I could articulate.

There was no clear sexual undertone. Except – except I just rewatched one of the videos I took after an early session, and it seems I accidentally misquoted some dialogue in Part 1. When Dr. K told me he’d read my breakup essay, the language he used was not “You weren’t lying” but rather “You weren’t faking it. You really weren’t faking anything.”

And I replied, god help me, “I never fake anything.”

I never fake anything.

In my defense I was on drugs and mirroring his language.

Then he asked if I was still in touch with my ex.

But maybe he just thought we had an intellectual connection, fellow creatives with wanderlust.

So why did I feel suddenly odd when I lay down on the couch in the cat room/Dr. S’s office for my next session and noticed just how clearly outlined my breasts were underneath my dress? I hadn’t worn a bra for comfort reasons. I suddenly wished that I had.

I had my package of lozenges in my purse. I didn’t know how I would explain taking them home with me. I figured it’d be a game-time decision.

But I didn’t have to say anything. Dr. K never noticed they were missing. He simply brought me a lozenge as if it were mine. He wasn’t keeping track, I realized. These prescriptions, which were supposedly compounded for each individual patient - they were all getting thrown into his stock.

I woke up from that trip to find Dr. K sitting in a chair across from me, reading The Pugilist at Rest.

This was better than him not being in the building at all, but it still felt weird in a way I couldn’t quite explain.

When I said I hadn’t read The Pugilist At Rest, he passed over his copy and told me to borrow it.

He had brought in another book to lend me that day as well – a story collection by West Virginian writer Breece D’J Pancake, who had committed suicide at 27. Dr. K said it reminded him of me, for reasons left unclear.

I tried to explain his behavior to my mom, but I could tell my descriptions weren’t helpful. She did not know what I meant when I asked if he got tongue-tied around her, if he struggled to get to the end of sentences and sometimes sounded like he was maybe on drugs himself.

So in a way it was a relief when, at nearly 11pm that night, my phone buzzed with a long message. He’d divided it into paragraphs. It was incomprehensible.

I passed my mom the phone and watched her eyes widen as she read and finally understood.

He said he hoped I was doing swell. He wanted me to look up the writing of his feminist writer friend and let him know if I wanted an introduction. And then he had some assorted thoughts – “loose talk and completely out of my wheelhouse but it’s after 10 PM so why not,” he wrote, going on to make some comments about the Barbie movie and the New York Times that I still can’t decipher, and something about the artist as an investment opportunity, and how given that his short story about mad cow and cannibals got him some interest in Hollywood, he hoped my agent had some feelers out for me because “female perspective material and media is going to be hot as shit for sometime to come.”

“Your stuff is really, really well groomed,” he said.

Was there anything sexual there? I wondered before realizing it didn’t matter; I was just accustomed to considering it when men caused me discomfort. It was what I was best trained to identify. But he didn’t have to want to fuck me to make me feel just as uncomfortable as I would if he did. It didn’t matter what exactly about him and his behavior was causing me discomfort. The point was the discomfort.

I felt sad for him for a moment, concluding that he must be pretty isolated and lonely to be texting me like this late at night. But also: he was my doctor. He had a duty of professional care toward me, and I had at no time indicated that I wanted more. He was sitting there at 11pm texting me about how to do my job, as if he knew my industry better than I did.

There was also this: half of his sentences didn’t make sense on a literal level. It was hard to avoid wondering something I’d wondered as early as my first session with him, when he asked me how I’d rate the intensity on a scale of 1 to 10 and I said 8, maybe 8.5, and he drawled, “that’s a good number, all the cool kids are wearing it on their shirts these days.”

Is this man on drugs?

I texted back: If only there weren’t a writer’s strike!

I left it at that.

My final session

I wake up alone. Again.

I’m in the cat room this time. It’s late, past 8pm. The receptionist is gone, her computer monitor off. There are two bottles of ketamine on her desk. The waiting room is empty.

I open the door to the little blue room and find a passed out man lying on his side, body pressed into the couch cushions. He looks unwell. I close the door immediately, go back into the cat room, sit down on the couch. Wonder: did I really just see a man in there?

There’s a slightly surreal feeling that lingers at the end of a ketamine trip. The world seems bright and slippery.

Maybe I imagined the man, I think. Surely Dr. K didn’t leave two incapacitated patients alone in the office.

I go back out, look around more carefully. I open the door again: yes, there’s the man. I haven’t seen what other people look like while they’re on ketamine, but my understanding is they usually lie still, on their backs. There’s something alarming about the way this guy is collapsed.

My first thought: this can’t be real.

My second: this can’t be right.

But what do I know about the ketamine scene?

I just know the way that guy is lying there looks bad, and there’s something wrong-feeling about the way we were put in different rooms and knocked close to unconscious with a combination of shots and lozenges and then left alone in an office building so after-hours empty that the custodian has just arrived to clean. She looks as startled to see me as I am to see her.

And then there comes Dr. K rushing in behind the custodian, trying to stop her from closing the door in his face.

“What the fuck, you left me alone again!” I say. My voice more high-pitched than usual. My fuck lacks bite.

“Sorry, sorry,” he says. He tells me that he went out to his car to get a book he wants to lend me, but the building doors lock after business hours, and he forgot his key, so he needed the security guard to let him back in, and the guard was off doing his rounds so he had to wait.

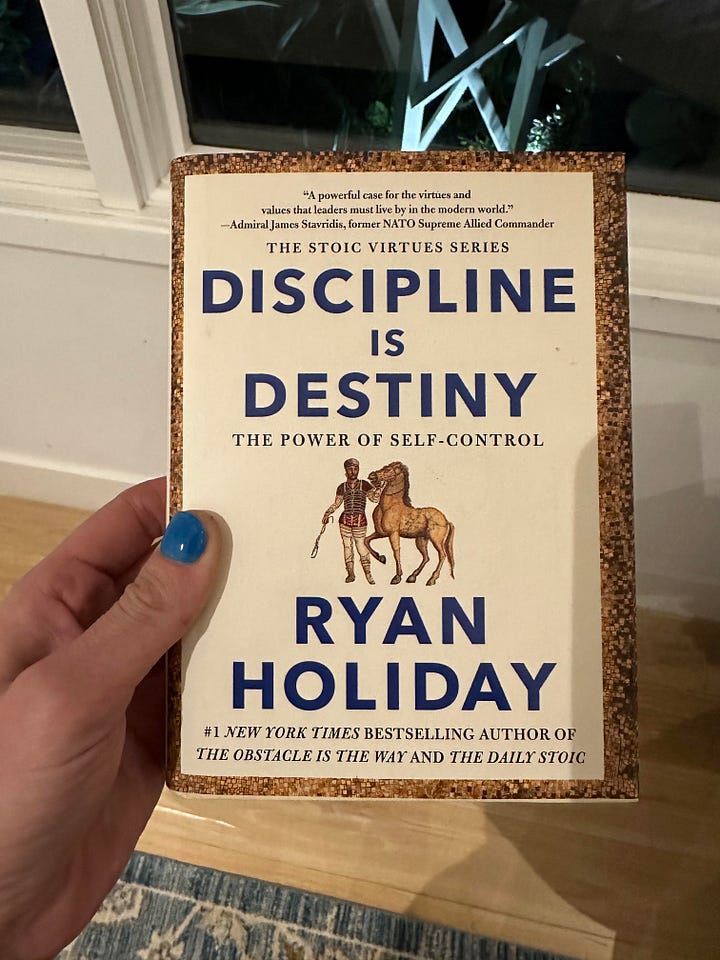

He passes me the book. It’s called DISCIPLINE IS DESTINY: The Power of Self-Control.

Part 3 to come soon! —

Groupers are amazing. They are my new favorite fish and I will never eat one again. They are curious about people and will follow you around throughout a dive.